A personal reflection, by Andrew L. Urban, October 23, 2016.

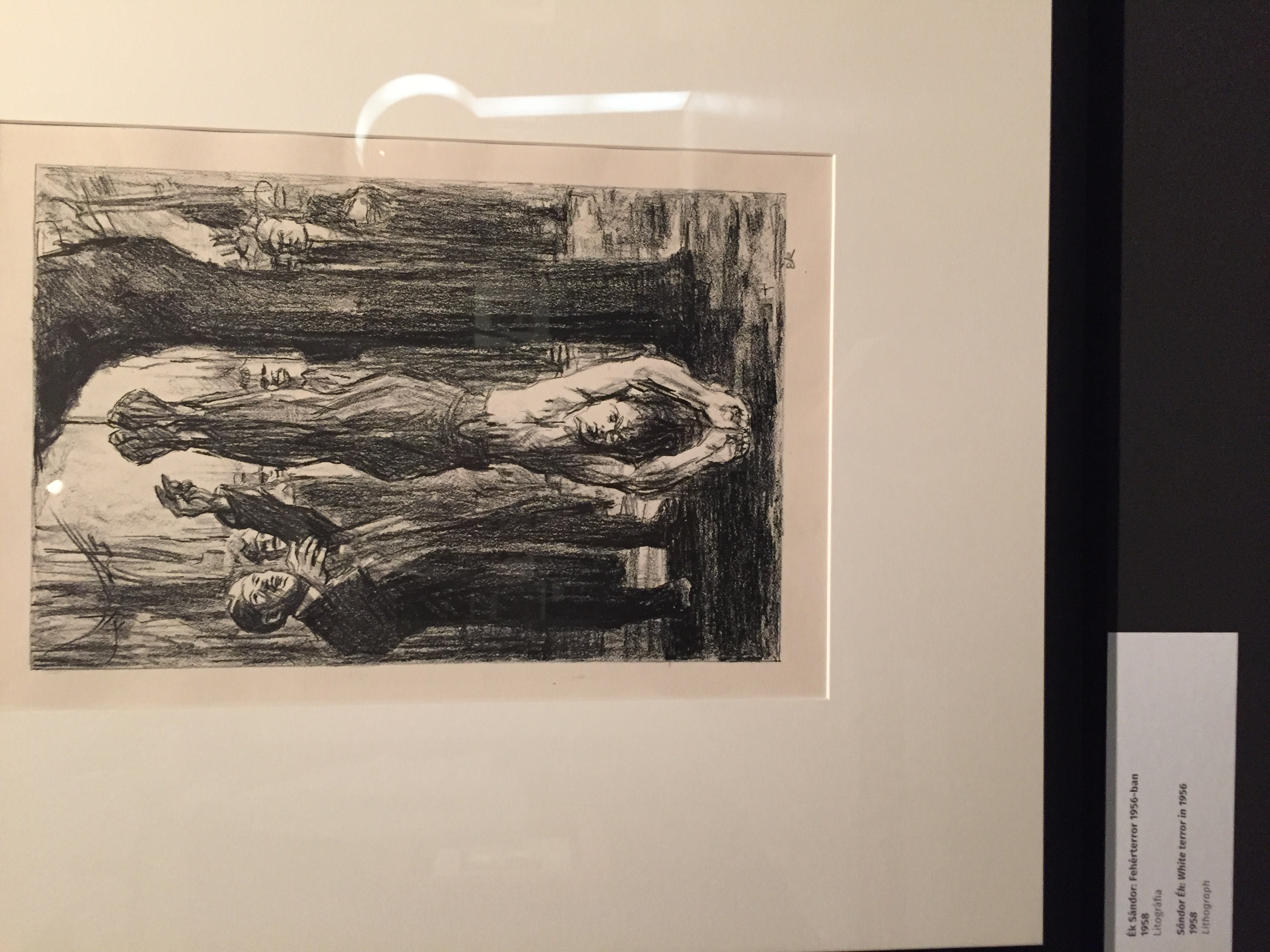

He was hanging from the tree by his feet, a wad of money stuffed into his mouth, the blood that had soaked it now dry. People were wandering around listlessly in the square, silent as were we, the autumn sky as grey and sombre as the mood on the ground. My mother and stepfather stood behind me as we took in the image and my stepfather quietly said one word: “Ávó…” the acronym for Hungary’s hated secret police (Állam Védelmi Osztály) had become a word, a word crippled with fear and loathing. This man had been one of them, and as he tried to flee the rage of the people, he was caught and executed, hanged upside down for eternal ignominy, his fat bundle of cash rammed into his face. Poor as they were, the mob wouldn’t touch money earned by a torturer, spy, traitor, enemy- and he wasn’t the only one they caught.

Soon, we moved on, to other images of death and destruction, the buildings riddled with bullet holes and tank shells. This is what late October and November 1956 looked like all over the centre of Budapest, in the wake of what came to be known as the Hungarian Revolution.

I am back in Budapest now, on the 60th Anniversary of the Revolution – October 23 – the causes of which (some of them) are housed in the city’s Terror House museum, filled with the paraphernalia of oppression and the black and white photos the world has seen of youngsters in the streets with guns, tanks menacing the population and ordinary citizens demanding freedom. The Terror House is at 60 Andrássy ut, the address which nobody wanted to visit when it was the headquarters of the AVO, its ghastly torture cells still filled with dread. It is now a memorial, too, to those who will never go there again.

The revolution lasted 19 days: ‘The 19 Days’ became the title of the book my father, Dr George R. Urban, wrote in the post-Revolution days of early 1957 in his rented Hampstead cottage in London, where he had lived since 1947, having got out just before the Iron Curtain closed off Eastern Europe. (Thanks to Mr Stalin and the deal he made with the Allied powers after the war.) The book, subtitled ‘A broadcaster’s account of the Hungarian Revolution’ is dedicated to me, who had just arrived in England as a refugee from Hungary. I was 11, the last time he saw me I was two. As a broadcaster at the BBC, my father had access to all the radio transcripts and clippings that reported on the Revolution, broadcast or written by the desperate Hungarians asking for help. The West, however, was distracted by the Suez crisis. No-one came to help.

Although I was at the time unaware of the Suez crisis, I was certainly not unaware of what the Revolution was about. Children living in politically unsavoury circumstances are quickly politicised. The oppressive, Moscow-directed Government and its savage agencies controlled the population through fear and secrecy. Spies were everywhere, often recruited with crude threats. We suspected our janitor was a spy. I was instructed never to speak to anyone about things I heard at home, such as what pigs our leaders were, how we hated the Russian soldiers and their tanks swaggering through the city, or the horrific rumours about friends or acquaintances who disappeared in the night. Would we be next?

We well could have been, what with my father working for the evil BBC, my maternal grandfather having been the head of anti-espionage before the war …none of us members of the Party… and little me refusing to wear the red kerchief of the Pioneers, a Communist bastardisation of the Boy Scouts. I relented when it was explained to me that without it, I would be noticed and questions would be asked of the family. Such small things could indict us all.

I had grown up fearful of the State, aware of the risks of politically incorrect words and actions, in a context that makes today’s notion of ‘politically correct’ risible. I say this in response to a blog post by Eva Balogh, a Hungarian living in the US, whose daily output is marked by a strident anti-Viktor Orbán /FIDESZ party stance. Writing about the 60th Anniversary celebrations, she publishes a 1956 photo of a young boy with a rifle and says: “these kids couldn’t possibly have known what the revolution was all about.” I beg to differ.

It is knowing the lived experience of Communism that informs us most accurately and realistically about it. All those Western intellectuals and writers who fell (and fall) in love with Communism from afar, harbour the romantic notion that it is a system of Government that ensures equality for all, reduces poverty and promotes harmony. The most polite response I have to that is ‘you wish’: it is the opposite.

I am writing this just streets from where I grew up, where on the evening of October 23, 1956, I was on an errand for grandma, when a truck full of people roared around the corner, shouting and waving… on the way to the inner city, via Heroes Square … ‘come on everybody!’ There was gunfire. Within earshot, people were killing other people with guns. This shocked me profoundly, and I felt a great, heavy sadness that humans could and would do that.

The first time I came to Budapest was in 1974 on my honeymoon, 18 years after we escaped. I had to see the apartment block I lived in, and curiosity must have driven me to gently slide aside the new nameplate next to the bell of our apartment. And there underneath was our old name-tag … for some reason I found this heartwrenching. Perhaps it was the melancholy memory of everything in my life that led up to October 23, 1956 and having escaped, saying goodbye to grandma …and for all I knew, goodbye to Budapest forever.

PHOTO; lithograph by Sándor Ék – White Terror – in the 60th anniversary exhibition at the Hungarin National Museum, ‘Secret Art of the Revolution’.