Andrew L. Urban.

Apart from the self contradiction in one sentence to the next, the unsourced statement on a Google page for the Hungarian Revolution, that the US requested but was refused freedom of passage through Austria is a total fabrication. It asserts as fact that the US wanted to take military action and it smears Austria as having refused to let them through. Neither is true.

On the eve of the October 23 anniversary of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, it is important to remember that historical facts matter.

Google – Hungarian Revolution 1956 – people also ask:

Why did the US not help Hungary?

There were several reasons why America did not act in Hungary: The United States asked Austria for freedom of passage to get to Hungary, but Vienna refused transit by land or even use of its air space. The United States had no plan for dealing with any major uprising behind the Iron Curtain.

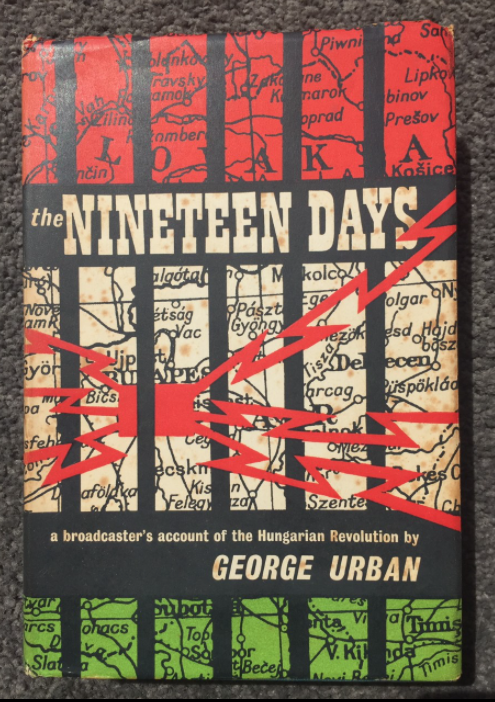

In his authoritative and well researched 1957 book, The Nineteen Days – a broadcaster’s account of the Hungarian Revolution (Heinemann) – my father, Dr George R. Urban, reports the relevant facts as follows:

In his authoritative and well researched 1957 book, The Nineteen Days – a broadcaster’s account of the Hungarian Revolution (Heinemann) – my father, Dr George R. Urban, reports the relevant facts as follows:

“At noon on Saturday November 4, (Head of the Austrian Legation in Budapest, Dr. Walther) Peinsipp handed (Hungarian Prime Minister Imre) Nagy an aide-memoir which must rank as one of the most important documents of the Revolution. Protesting that no armed or unarmed Hungarian emigres had infiltrated into Hungary through Austrian territory (in response to allegations coming from East Germany and the Austrian Communist press) the Austrian Government stated that it had ‘ordered the establishment of a closed zone along the Austro-Hungarian frontier. Only authorised persons, such as local inhabitants, Red Cross personnel, who are staying there officially, and journalists, are entitled to admission. The Minister of Defence has inspected this zone in the company of the military attaches of the four Great Powers, including the USSR. The military attaches were thus able to see for themselves the steps which had been taken in the frontier area to protect the Austrian frontier and Austrian neutrality.”

The so called four Great Powers at the time, of course, included the US (along with the USSR, France and the UK).

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 provided an unexpected opportunity for Austria to test their newly acquired independence, wrote Martin Pemmer on the Revolution’s 50th anniversary. “Just one year before, the country had regained its full independence and was confronted with the challenge of fulfilling the conditions of self-declared “neutrality.” The remarkable role played by the Austrian diplomatic mission in Budapest in launching a humanitarian campaign, however, is largely unknown.”

Pemmer reports: “Hundreds of tons of food, medicine, blood plasma, bandages, clothing, and other supplies were collected and brought to Hungary beginning on October 27. The call for humanitarian assistance happened spontaneously, often without institutional support, directives or a central organization, and especially during those few short days before the Soviets intervened for the second time on November 4. Hundreds of trucks and cars bearing the label of the Red Cross crossed the border, still open at Nickelsdorf, bringing with them donations to Budapest and Györ which were gratefully received by the Hungarian population. Much of the supplies were delivered to various hospitals, schools and homes …”

It was later ascertained by the American journalist, Leslie Bain, that Austria’s Legation in Budapest was the only diplomatic representation that carried out any substantial humanitarian action.

As a young refugee from Hungary at the tail end of the Revolution through Austria, where I received the kindest and most generous welcome, I can not let Google misrepresent that country and its people.

It is worth noting in this context that United States Secretary of State under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 to 1959 was John Foster Dulles, a significant anti-communist in the Cold War. Writing in The Nineteen Days, Urban Snr states: “he considered a fully free and independent Hungary a dangerously unrealistic proposition, so much so that in the final stages of the Hungarian Revolution he let it be known to Prime Minister Nagy that his overtures to the West were too openly friendly; altogether, could his Government slow down a little and not embarrass the Russians.”

Nor did the British have plans to intervene, as Hugh Gaitskell, Leader of Britain’s Labour Opposition at the time made clear in a lecture, as my father’s book reminds us. “The plain fact is that in our defence planning and its political framework, we did not envisage such a situation developing out of a rising behind the Iron Curtain ….For us to take the initiative in breaking through the Iron Curtain to help people on the other side of it was a prospect for which we had never really provided.”

24 hours after this post was published, the entry on Google was taken down.