Andrew L. Urban

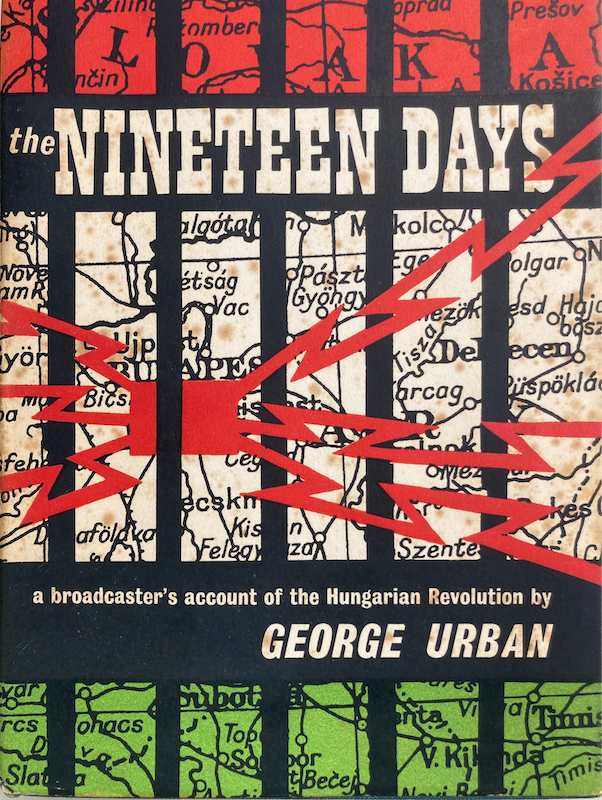

Marking the 65th anniversary of the Revolution, we delve into the pages of The Nineteen Days, ‘a broadcaster’s account of the Hungarian revolution’. That broadcaster was my father, George Urban. The book was written in the immediate aftermath of the revolution, my father sitting at his trusty typewrite in a Hampstead cottage, while I floated around in childish joy at my new-found freedom as a refugee in London. The following excerpts document a significant time in the Revolution: Point of No Return.

The world gasped 65 years ago this week as Hungarian protesters were mowed down by the secret police, starting a revolution that took Soviet tanks to crush 19 days later. The images of street battles that came out of Hungary during the fighting left unsaid the deeper story of why and how it came to be. Even now, many people don’t know how the fuse was lit long before, why the bloodshed began and what it showed about the underlying political weakness of Communist regimes

The Nineteen Days paints a clear picture of the events which took place in the 19 days between October 22 and November 9, 1956, hour by hour and day by day, drawing on eye witness accounts, excerpts from Communist press and radio, and from the insurgent radio broadcasts which were sent out from Hungary while the freedom fighters were in action.

The Nineteen Days paints a clear picture of the events which took place in the 19 days between October 22 and November 9, 1956, hour by hour and day by day, drawing on eye witness accounts, excerpts from Communist press and radio, and from the insurgent radio broadcasts which were sent out from Hungary while the freedom fighters were in action.

My father was then working at the BBC, who generously allowed access to and free use of BBC material. The profits of the book were divided between The Lord Mayor of London’s Relief Fund for Hungary and St Benedict’s School, Ealing – where I spent three years learning English and attempting to gain an education.

In his author’s preface, Urban Snr writes: “Few upheavals in modern history have bequeathed such a clear and articulate message to posterity as the Hungarian Revolution.” He wrote: “That a superficially liberalised version of a doctrine that continued to be false and oppressive should pass for freedom, Socialism, and democracy – this was the nightmare from which the heroism of the men, women and children of Hungary have freed us.”

In his author’s preface, Urban Snr writes: “Few upheavals in modern history have bequeathed such a clear and articulate message to posterity as the Hungarian Revolution.” He wrote: “That a superficially liberalised version of a doctrine that continued to be false and oppressive should pass for freedom, Socialism, and democracy – this was the nightmare from which the heroism of the men, women and children of Hungary have freed us.”

What follows is a selection of excerpts from the chapter, Point of No Return, which in a nutshell relates both the big picture and the minutia of this milestone event in history. The first shudder of protest was felt on October 23, as Uni students gathered to demand a list of new freedoms. The government response was aggressively negative.

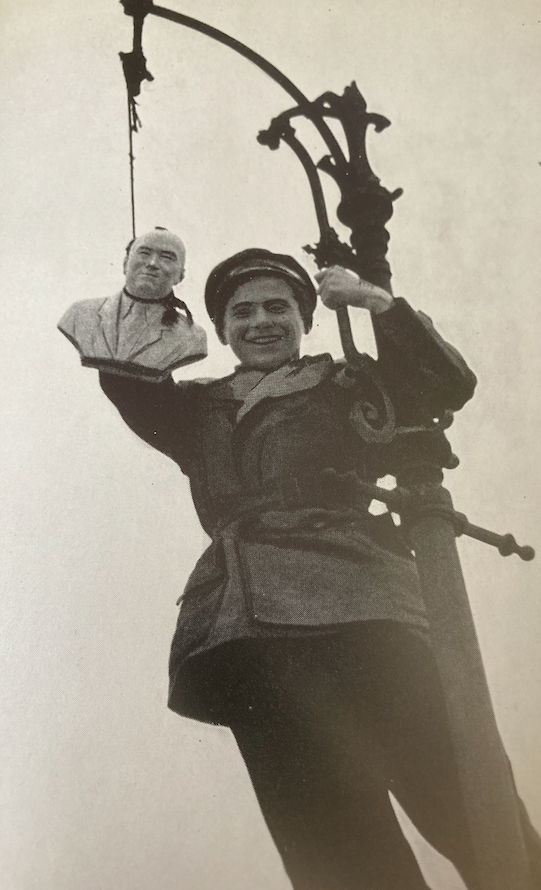

Violence erupted. The enraged crowd marched on to tear down the enormous statute of Stalin, symbol of Soviet oppression, and decapitated it.

We pick up the story on the night of October 24/25, with the disorganised Hungarian army in Budapest standing guard at the bridges over the Danube (without ammunition), until they were replaced by Soviet armour. But at the same time, there were signs that the Soviet tank crews were looking for an excuse to stop fighting.

OF TANKS & BREAD

One pertinent reason for the poor fighting spirit of the Soviet tank crews was their supply position. They were expected to be able to live on the land or buy food in the shops. Faced by a hostile population, they could not do either. It did not take them long to discover that only arms and ammunition could buy the precious articles and that the men to contact were the freedom fighters. It is difficult to overestimate the part which the Russian’s foods shortage played both in undermining their own loyalties and raising the hopes of the population. In the capital and later in other cities and industrial centres, guns and even tanks were freely offered to the freedom fighters and the population in exchange for a few loaves of bread. The evidence that comes from a young worker from Miskolc is typical of many similar cases:

“I was on my way to X when I saw two Russian tanks come up behind me. I was carrying two loaves of bread and about a kilo and a half of sausages. The Russians in the tanks must have seen that I had food in my basket. They stopped and one of them got out. He carried an automatic. He knew a little Hungarian as he had been in the country for some time. As far as I could make out, he asked me to give them my loaf and offered his tank in exchange. He looked completely starved. I took a loaf from my bag and cut a chunk for them. We talked for a while. Then he began to ask me for the rest of the food I was carrying. As they had the guns and I had nothing, I gave them all the food I had. Then I said to him, “Give me a gun.” He gave me his automatic with 14 bullets. When they got the food, he and another one who had joined him, began to weep. They told me they would take me home. I said there was no need to do that. I would go on my own. The first Russian then told me that they would like to come with me. They would do any work as long as they were allowed to stay in Hungary. If they were sent home, they would be liquidated. Of course, I couldn’t take the tank. I didn’t know how to drive it, and even if I did, what would I do with a tank single-handed? So I said to them, “Look, boys, I don’t want your ruddy tank. All I wanted was a gun and I got that.” But they didn’t think it was a good idea to stop there talking to me. So, I said goodbye to them and walked off.”

“I was on my way to X when I saw two Russian tanks come up behind me. I was carrying two loaves of bread and about a kilo and a half of sausages. The Russians in the tanks must have seen that I had food in my basket. They stopped and one of them got out. He carried an automatic. He knew a little Hungarian as he had been in the country for some time. As far as I could make out, he asked me to give them my loaf and offered his tank in exchange. He looked completely starved. I took a loaf from my bag and cut a chunk for them. We talked for a while. Then he began to ask me for the rest of the food I was carrying. As they had the guns and I had nothing, I gave them all the food I had. Then I said to him, “Give me a gun.” He gave me his automatic with 14 bullets. When they got the food, he and another one who had joined him, began to weep. They told me they would take me home. I said there was no need to do that. I would go on my own. The first Russian then told me that they would like to come with me. They would do any work as long as they were allowed to stay in Hungary. If they were sent home, they would be liquidated. Of course, I couldn’t take the tank. I didn’t know how to drive it, and even if I did, what would I do with a tank single-handed? So I said to them, “Look, boys, I don’t want your ruddy tank. All I wanted was a gun and I got that.” But they didn’t think it was a good idea to stop there talking to me. So, I said goodbye to them and walked off.”

PARTY SPIN

An example of the sort of thing that constantly happened in the street fighting, is given by a 20 year old insurgent, whose closest contact with war had been the drums he had transported for a musical society. “We saw a troop of four tanks come down the road on the morning of the 25th. We let the first three pass, the fourth, which was a self-propelled gun, was attacked with petrol bombs and hand grenades. The vehicle was not on fire, but the crew must have been so frightened that they jumped out and gave themselves up. Fortunately, the three tanks that were in front could not see what had happened behind them. Among the freedom fighters, we had army reservists, who knew exactly how to cope with the gun. We followed the Russian tanks. They had no idea that the self-propelled gun was in our hands.

We were a bit frightened because we thought that in turn, we ourselves might be attacked by the freedom fighters. The Russians drove up to the Hotel Astoria, turned left and drove along to Calvin Square. Here, they turned sharp right into Kecskemeti street. We knew that our chance had come. As the first two tanks disappeared around the corner, we took aim and destroyed the third Russian tank from the rear, just as it was about to turn the corner.

At 5:00 AM on Thursday 25, October, the Party and the Government as good as buried the revolution. A communique issued over Radio Budapest announced that ‘the Army, the state security forces and armed workers’ guards have liquidated, with the help of Soviet troops (the ones already stationed in Budapest), the attempt at a counter revolutionary coup d’etat on the night of 24/25, October. Three hours later at 8:15 AM however, the minister of defence, Barta, ordered the armed forces completely to eliminate by midday, the counter-revolutionary gangs, still to be found in Budapest.’

At 10:47 AM, radio Budapest warned the population that, although order had been almost completely restored, certain irresponsible elements were still firing shots in the streets. The population was advised not to go out. At 11:33 AM, the first momentous political change in the constitution of the Hungarian Communist Party was announced. The Politbureau, that had consisted since the 24th, of a mixture of Stalinists and Gero himself and Nagy’s men, dismissed Gero from his post of First Secretary of the Central Committee and appointed Kadar in his place. Kadar’s speech that followed the announcement moved in broad generalities. He repeated his earlier thesis that the demonstration on the 23rd had started peacefully, but later degenerated under the influence of counter-revolutionary elements into an armed attack against the people’s power. No one could wish to have the people saddled again with the old yolk of capitalist bankers and landowners.

By the time Nagy, who was still a prisoner of the AVO, came to the microphone at 2:25 PM events in the streets of Budapest had given the revolution a completely new turn. The Party’s effort was now concentrated on canalising the uprising into channels that were acceptable to Moscow. Nagy with his reputation as a good Hungarian and the moderate leader seemed the only available communist who could be trusted to contain the revolt within the bounds of national communism. Earlier, on the 25th Mikolyan and Suslov flew to Budapest and, possibly under their direction, a program had been worked out for Nagy to put before the nation. Nagy admitted that serious political and economic mistakes had been committed in the past. The new leadership of the party and his government were determined to draw the lessons to be learned from the tragic events.

He was proposing a broad Popular Front, an amnesty and talks with the Soviet Government for the withdrawal of Russian troops from Hungary. These talks would be carried out on the basis of equality and national independence. He added, however, that the intervention of Soviet forces was necessary because Hungary’s ‘Socialist order’ was threatened. Russian troops would be ‘ordered back’ as soon as peace and order were restored.

There can be no question that on the 25th, the Soviet leaders still thought that with concessions of the sort Nagy was made to hold out, the situation could be saved. The 25 October issue of Pravda began a smear campaign in a dispatch from Budapest. After claiming that the rising was a ‘counter-revolutionary’ rebellion against the people’s regime, ‘organised by underground reactionary bodies’, the dispatch went on to speak of unbridled, fascist thugs who had begun looting, smashing windows, and destroying industrial equipment. But Pravda restrained itself from associating Nagy with the ‘counter-revolutionary’ elements and stressed that the situation was in hand. No concessions, however, were made on the one point that would have offered any prospect of stabilising the situation; the withdrawal of Soviet troops. Broadcasting to its home listeners on the same day, Radio Moscow made no mention of Nagy’s reference to negotiations with the Soviet Union about the withdrawal of Russian forces. While supervising the general trend of events in Hungary from close quarters, the Soviet leaders, during this period left the Hungarian communist to make most of the running.

The Kremlin itself was very far from being certain in its reactions. The Soviet Foreign Minister, Shepilov, declared in Moscow the same day that the difficulties in Hungary had been caused by bureaucratic methods of administration and the ‘material conditions’ of the people. There had been a demand for democratisation. This, he said, had led to demonstrations, which certain forces had tried to exploit. A Soviet news agency, (Tass) account of the insurrection however, reported on the same day that the trouble in Hungary was due to the forces of foreign reaction. It claimed that the disturbance had been prepared well in advance. Soviet units had intervened at the request of the Hungarian government, but in the meantime, order has been restored.

DOWNPLAYING A REVOLUTION

Hungarian flag with the communist emblem ripped out by freedom fighters

At the time when Hungary was front page news in the world, press and radio, Radio Zagreb and Belgrade gave as little prominence to what was going on in the capital of the country’s northern neighbour as they possibly could. In a transmission in Bulgarian on the 24th, for instance, news of events in Budapest was broadcast as the fifth item in a program of nine. And the Novi Sad transmission in Hungarian at 11:00 PM on the 24th carried a four minute round-up based entirely on the appeals, threats, and situation reports of radio Budapest. On the 25th Borba’s (Belgrade based news outlet) commentator pointed out that the democratisation of life in Hungary must be speeded up in keeping with the ‘tendencies’ of the working class. He expressed the view that one of the reasons which led to the shedding of blood in Budapest was the fact that the former party leadership did not react in time to the demands of the people. Eventually, Borba maintained irresponsible elements turned the students’ peaceful demonstration into aimless armed action. Counter-revolution appeared and in the event, many honest, well intentioned people, mostly workers, youths, and students, found themselves on the wrong side of the barricades, sacrificing their lives in a struggle that had nothing to do with their ideals.

POINT OF NO RETURN

There was no shortage of news or comments from the western broadcasting stations. The admiration, which the free peoples of the world felt for the heroism of Hungary and the horror with which they received the news of Soviet armed intervention, were fully reflected in these transmissions. At 4:45 p.m. on 24 October, the BBC for instance, said in Hungarian, “clearly the use of force does not solve the problem. It merely aggravates it. A return of something like the Rakosi regime at the point of Red Army bayonets would be disastrous not only to Hungary, but also to the Soviet Union.

A bust of Rakosi on a lamp post in Gyor

Already, the use of force against the Hungarian people must have dealt a heavy blow to the Soviets standing with the neutralist and the colonialists and uncommitted peoples. President Tito, although he would not like to see communism overthrown in Hungary, certainly cannot be pleased to see the Red Army in action, imposing Soviet domination on his borders. His counsel will presumably be for moderation and for an attempt to undo the evil effects of this day’s work. Fortunately, Mr. Nagy, too, with his promises of an amnesty and the future reforms, seems inclined to attempt the path taken by Mr. Gomulka. The question, of course, is whether he will not be too compromised by the Red Army intervention and the presence of so many Muscovite communists on the Politburo to carry this through.”

At 7:30 p.m. on the same day, the BBC commented, “To talk about foreign provocation at a time when the new leader of the Polish Communist Party freely admitted that the Poznan disturbances had nothing to do with foreign initiative, but were entirely the result of the wretched conditions of the Polish workers, shows that Mr. Gero and his supporters still cling to the outworn cliches of communist propaganda.” On the 25th, the BBC gave extensive summaries of the British morning press and at 4:45 p.m., an editorial of the Manchester Guardian was condensed for listeners in Hungary.

“After East Berlin Beria went,” the BBC said, quoting The Guardian, “after Poznan, justice came back; after Budapest, though the government – unlike Mr. Gomulka, -is blaming ‘counter-revolution’ rather than itself, something else must change. As a way of winning back a decent life, it is terribly painful. We dare not recommend it. We should, on the contrary, counsel patience to those whom we cannot help, but we must salute people who are fighting their way back into Europe. A Europe that knows neither east nor west.”

At 7:30 p.m. on the 25th, although still unaware of the full significance of the massacre in Parliament Square earlier in the day, the BBC commented on Hungary’s ‘Moment of Truth’. The BBC said: “Now, the Hungarian authorities, by dismissing the Stalinist Gero, have recognised that the lie cannot be reimposed. And that, at least in part, the truth must prevail. Of course, this is only a beginning. All through Czechoslovakia the communist agitators are busy giving a totally false picture of the events in Hungary. Radio Moscow itself did not tell the Soviet people of the intervention of the Red Army for nearly 24 hours and when it did so, it spoke of a fascist counter-revolutionary revolt against the people’s regime… Clearly, it will be a long time before the truth penetrates the citadel of the empire of lies. But the Soviet leaders, if in their own interest, they want to restore order and stop further bloodshed, will at least have to come to terms with the truth. That may not mean that the peoples of Eastern Europe will get all the liberties which they desire and have a right to. Even in Poland and Yugoslavia, that clearly is not in sight, but at least they can no longer be used as pawns in a monstrous game of deception. In that sense, truth is on the march.”

The majority of these comments were also broadcast in other central and east European languages. In the course of the following days, the BBC explained why, in the case of Hungary and Poland, the Soviet news blockade, under the present collective leadership, remained enforced to the same extent as under Stalin. It was shown how the anti-communist uprising in Hungary coming so soon after the ferment in Poland aggravated the ideological crisis in which the various communist parties had found themselves since the 20th Soviet Party Congress. And in the broadcasts beamed to Russia and her remaining satellites news and comment on Hungary and Poland were given pride of place throughout the revolution. This was the political landscape in and around Hungary on the day that proved to be the turning point of the revolution. Before Gero’s dismissal was announced at 11:33 a.m., listeners to Radio Budapest were asked to believe that all was well in the capital.

At 9:00 a.m., a reporter said that transport workers had gone back to work. Five minutes later, the radio announced that the dairies had resumed deliveries to the shops. That the Budapest City Council had told the managers of food shops to keep their shops open all day. That work had been resumed in the great market hall, although there was a shortage of porters to unload the lorries, and that 60% of the government-controlled Kozert food stores in the city and 80 to 90% in the outskirts were open. An uninterrupted supply of flour, bread, sugar, and potatoes would be available by the afternoon, Radio Budapest promised 10 minutes past nine in the morning. The cotton workers of Pamutipar were said to have reported that work had begun in the factory. “Afternoon and evening shift workers are asked to report for duty,” the radio announced, but 36 minutes later, it warned the population of Budapest that, until further notice, a curfew was still in force between 5:00 p.m. and 5:00 a.m. But between 10 and 11 that morning, the people of Budapest, incensed by the tone of the radio station, were assembling for another demonstration.

The Radio Building – reclaimed by the freedom fighters

“On Wednesday, the students had been sent an ultimatum to surrender, but, of course, they did not obey. The Russians had made several attempts to take the place without success. Outside, a proper battle was being fought. The houses were rocking with gunfire. It lasted about 10 minutes. Then, suddenly, shouts were heard from the museum. ‘Come out quickly. Something wonderful is happening.’ People brave enough to come out from their hiding places were calling down the sellers. By the time I arrived on the scene, the Russian tanks were ringed by huge masses of people cheering and waving handkerchiefs. I was trying to find out what exactly had happened. Apparently, the Soviet tanks, which were in constant radio communication with each other, had suddenly ceased fire, opened their turrets and put out the white flag. On the top of one of these tanks, a Hungarian interpreter was translating the words of a Russian officer.

“The tank crews were trying to say that they knew perfectly well that the Hungarian people were fighting for their freedom. They respected our cause and they had only fired on us because they had been ordered to do so. As this message was translated bit by bit into Hungarian, more and more people arrived. Hungarian flags were hoisted. Young men jumped on the tanks and led by Russian armour, the crowd started for the inner part of the city. Leaflets showing the revolutionary program were distributed. The Soviet crews stayed on top of the tanks and our own people were also there with them. This was one of the precessions that marched to Parliament Square that morning.” Similar things happened in various parts of the city. A 39-year-old textile worker who had spent several years in a Russian political prison and spoke the language fluently, reports: “Some of us who spoke Russian and others who had picked up a smattering at school, thought it was now time to use it. God knows we had paid a heavy price enough for it. On the morning of 25 October, I was outside the Hotel Astoria, an important road junction which 16 Soviet tanks kept under control. This was really a nerve centre of Russian armour in the city. From here, orders were issued to the areas where fighting was taking place. That is, the radio building, the National Museum, Calvin Square, and the ring road. A woman friend and myself started talking to some of the Russian soldiers who were hiding behind sandbags. We wanted to win their confidence.

“We told them that the people of Budapest were not fighting the Soviet Army. They were trying to get rid of the intolerable Rakosi-Gero clique. As we were talking, a crowd of perhaps four or 500 people carrying a whole forest of flags, came marching down from Rakosi Road, taking up the whole width of the pavement. They were singing the Kossuth song and the national anthem. The scene was so moving that when we saw the Soviet tanks training their guns on demonstrators, we both began shouting at the Russians, begging them not to fire on a group of unarmed Hungarians who wanted nothing but their freedom. Whether it was due to this or some other reason I do not know, but no shots were fired. I could see that some of the Russians were overwrought with the singing and they allowed the crowd to come right up to the tanks.

“Just then, something completely unexpected happened. Young men and women jumped up on the tanks, offering cigarettes to the Soviet soldiers. My friend and I, again pleaded with the Russians not to hurt anyone because the people were friendly towards them. In no time, Hungarian flags were fastened to the turrets and hung from the aerials. The men who were apparently in charge of the demonstration asked us if we could persuade the Soviet commander to allow the tanks to join the crowd in a demonstration outside Parliament Building. This officer was a Siberian. One could see he was furious. Why had he not ordered the tanks to fire when the crowd was still at a distance? Now, he was helpless. On his own tank, there were about 30 men, women, and children yelling and waving flags. They were obviously in full command. He replied that he had no orders and would not help the demonstrators.

“When we realised he wouldn’t play, we tried negotiating with the men in charge of each tank. Eventually, two of the crews agreed to join us and two more said they were willing to let Hungarians drive their tanks, provided that they, themselves, could stay on. So, this is how things happened. The procession started out for Parliament Square led by two Soviet tanks. These were followed by an armoured car and another tank, which was manned by Hungarian veterans. The other 12 tanks stayed behind, but the commander promised that he would not destroy the tanks as they moved off or fire on the crowd. He kept his word. On the same day, about 30 Soviet tanks and armoured cars joined the freedom fighters. The Soviet troops who had been stationed in Hungary were in strong sympathy with us and it was not too difficult to convert them. Between 9:30 and 10:00 a.m., thousands of men and women waving flags and shouting, ‘this is a peaceful demonstration. The radio is telling lies. We want to be free,’ converged on Parliament Square from various directions.

“About 2,000 people passed in front of the United States Legation. They saluted the American flag and some shouted to the Legation, ‘why don’t you help us?’ From other directions, large processions arrived escorted by Russian tanks and armoured cars, and the crews were fraternising with the demonstrators. No Hungarian soldiers could be seen. Few people noticed the barrels of the security police machine guns that were waiting for the demonstrators in the windows of the Ministry of Agriculture and other neighbouring houses. The tragedy that followed is described by a young woman. “When our column arrived from the Bajcsy-Zsilinsky Road (about 5 – 6 blocks), we found an immense crowd waiting outside Parliament House. We were singing the Szozat and the national anthem. We had three or four Russian tanks in our part of the procession. The Russian officer who appeared to be in charge stood on top of one of them. He was surrounded by young Hungarians, and the children and women were kissing him. His tank flew the Hungarian national flag. The Russians cheered and waved as they moved along with the crowd. I heard that they were telling the crowds that the Soviet forces had no intention of going on fighting the people and it was rumoured that they had been ordered back to base.

“When we arrived in front of the Parliament Building, I bumped into an uncle of mine, a doctor who had been carried along by the crowd from the direction of Nador Street. He, too, came largely out of curiosity. What, in fact, was happening was that the students and workers were protesting because the previous day, the communist radio had called them fascists and counter-revolutionary thugs. The various columns arrived in perfect order, completely unarmed and in good faith. Suddenly, heavy machine gun fire was opened from the windows and the roofs of the Ministry of Agriculture and the neighbouring blocks. There were no speeches and no warning was given. The time was about 11. First, the security police aimed at our knees. Their intention must’ve been to force us to the ground. The singing stopped. There was no panic. Only a deep, deadly silence. There was no covering the square, nor was there room to move. Then the massacre began. The AVO’s positions must have been prepared well in advance because, as I looked up, I saw barrels of machine guns jutting out from well-arranged positions. They had expected us. I stood on the left side of the square facing the Parliament Building as my part of the procession had come from Bank Street.

“It was a dreadful experience. I could see the bullets catch people in the shoulder and in the jaw. Sometimes, the linked arms of young couples were shot away. Then, there were people lying in their blood, praying and crying. There was complete disorganisation, but no terror amongst us. Only deep shock and utter bewilderment. Was this possible in the 1,956th year after the birth of our Lord? My uncle was trying to give first aid, then the ambulances arrived, but they, too, were shot at. Anyone who moved was in mortal danger. Next to me was a young boy with a bad lung injury. He was whispering for water. I tried to raise myself on my knees, but immediately bullets began to whistle past me. It was impossible to move. Then, somehow crawling along the ground, the doctor helped him, but there was little he could do.

“There was a Soviet tank nearby. The Russians were just as shocked as we were and when the AVO men began to shoot at the doctor, the Russians inside the tank returned the burst of machine gunfire into the building. It was complete chaos. The Russian tanks that had come with our procession were on our side throughout the firing. In the meantime, however, further squads of Russian tanks moved up from the direction of the Ministry of Defence. Some people said that they had been called out to help the AVO (acronym for the secret police). Others thought they were on patrol and when they heard the shooting, they assumed that there was a clash between Russian tanks and armed demonstrators. The new arrivals lined up and began mowing us down from another direction.

“The three-cornered fight went on for a good hour. The AVO were shooting from the buildings. The rebel Russian tanks were shooting at the AVO. And the tanks that had come from Ministry of Defence were shooting at the crowds and the Russians who were helping us. Most people who were hit died instantly. Some were removed in ambulances, though there was no pause in the firing. I remember a moving little scene. Many personal belongings were lost as everyone stumbled and fell over each other. A Russian who had been watching the doctor and myself as we were trying to help the wounded picked up a handbag from among a horrible mass of groaning and helpless people, opened it, took out a lipstick, and offered it to me as a token of his respect.”

Far from deterring, the massacre embittered and inflamed the demonstrators.

****

By October 30, freedom seemed a heady reality; “the four Soviet garrison divisions were either defeated or so weakened in their morale that their fighting efficiency was inadequate for further action.” Then at dawn on November 4, new divisions of Soviet tanks and troops arrived to crush the revolution, ‘at the request’ of Moscow’s newly installed puppet Government of Janos Kadar.

In that brief shining moment of freedom – a few days between the success of the freedom fighters and the crushing of the revolution by Soviet forces – the people of Budapest were free to move around the city, witnessing the aftermath of the fighting, dazed by the thought of a future without the permanent terror of the secret police. Seared into my memory is the sight of a member of that hated and feared cohort hanging by his feet (the traitor’s death) from a tree in a battle scarred city square, dried blood covering much of his face, a bundle of his blood money stuffed into his mouth.

SO VERY IMPRESSIVE ,BUT JUST TO THE REAL POINT OF ACTION ……..THE TRUTH ….I WAS THERE BUT ONLY A7 YEAR OLD ,TEENAGER ,IN LOVE WITH A 18 YEAR OLD MEDICAL STUDENT .

WE HAD TO LEAVE ,,,,SO WE DID TO START OUR LIFE TOGETHER IN A PEACEFUL COUNTRY , ENGLAND .