Andrew L. Urban

Two movies, screening in early May (in Sydney) and a Guantanamo Bay court hearing the case of Southeast Asia’s once most wanted terrorist, each confront the vexed issue of how society punishes terrorists.

Is a terrorist a criminal? I argue not – not as we mean it. Crime is committed for personal gain. Terrorism is committed for ideological gain. Criminals do not wish to attack western society. Terrorists do.

These are significant differences and if the punishment is expected to fit the crime…we haven’t figured out what that punishment might be. How could laws against crime be useful against terrorism? It’s a challenging issue, I admit.

Does a killer who murdered his/her partner deserve the same, say, 20 year jail time as a terrorist who killed dozens of innocents?

Consider the case of Encep “Hambali” Nurjaman. The now 59-year-old Indonesian-born alleged mastermind of the deadly 2002 Bali bombings and 2003 Jakarta Marriott bombing who was a close associate of 9/11 al-Qa’ida mastermind Khalid Shaikh Mohammed and Jemaah Islamiah founder Abu Bakar Bashir. He was formally charged only last year and is facing trial alongside two Malaysian citizens on the US naval base of Guantanamo Bay on charges including conspiracy, murder, attempted murder and terrorism. Hambali has been held in Guantanamo Bay since 2006 after spending three years being tortured for information at CIA black sites around the world, according to a 2014 US Senate report.

His alleged key role in the 2002 Bali bombings led to the deaths of 202 people including 88 Australians. He is also alleged to have played a key role in the Jakarta Marriott Hotel bombing the following year which killed 12 people and left up to 150 injured. At hearings in late April, prosecutors proposed a formal trial date of early 2025, more than 21 years after his arrest in Thailand. It’s either cruel delay or a function of a system that is not designed to treat terrorists. Wearing traditional Islamic dress, he appeared to be smiling and laughing as he entered the courtroom in Guantanamo Bay. Do we expect him to ever abandon jihad? To be rehabilitated?

There is no appropriate punishment system to apply to terrorists in the contemporary world. What, for example, would be appropriate punishment for the perpetrators of the Charlie Hebdo murders? The deterrence aspect of prison simply isn’t relevant to terrorists. Nor even is death. What’s left?

When Barack Obama became President of the US, he vowed to close down Guantanamo Bay where Islamic terrorists were being held. It was a well meaning but ignorant attempt to treat terrorists with misplaced compassion. It proved impossible to do, because the threats posed by released terrorists are uncontainable. That’s the crux of why punishment for terrorism should not be jail terms like for any other crime. The enormity of terrorist action in terms of potential innocent human suffering is far greater than criminal behaviour and far less containable.

Retired US Red Beret Master Sergeant Terry Schappert has spent almost 25 years in the Middle East. “I’ve lived with Arabs,” he told Fox News, “I’ve trained their soldiers, I’ve fought with them, bled with them, I’ve watched them die. I was a Green Beret medic; I’ve delivered their babies, I’ve pulled their teeth, I’ve inoculated their farm animals. You’ve got to understand them, how these folks think. They’re worried about their family, their clan and their tribe. They don’t have a national identity.

“…the guys who are living here in the West … the killers. What do they care about? They hate the country they live in. What they care about is their family; they care about that group. So any time any of these guys does this (act of terrorism) their whole family should get picked up and deported, back to the country of their origin. You take from them what they care about and it would slow them down, if not stop them…”

In a democratic country, that approach would not be permitted by law.

Meg Smaker

Deradicalization is the only ‘cure’ that has been tried. The documentary titled The UnRedacted – Jihad Rehab is the story of “a group of men trained by al-Qa’ida transferred from Guantanamo to the world’s first rehabilitation centre for “terrorists” in Saudi Arabia.” After its US tour of one-night stands (also Auckland and Melbourne), the film had its only Sydney screening at the Chauvel on Friday, May 5, followed by a Q&A with American filmmaker, Meg Smaker. The inverted commas around the word terrorist in the promotion is a clear signal that the filmmaker is not totally convinced her documentary is dealing with terrorist. They are portrayed as guys who went off the rails. All the same, it is interesting for the (mostly shallow) insight they offer of their activities. Some questions are evaded.

Nick Allen writing for the Roger Ebert movie website from Sundance 2022 had the same response: “Empathy can be an inherent part of the documentary form, but it seems to have been a speciality during this festival. The US Documentary Comp(etition) is full of stories in which filmmakers find a story in which they recognize a person’s complicated experience, and then try to pass that on for the viewer. One of the most intense, polarizing examples can be found in Meg Smaker’s stunning “Jihad Rehab,” which profiles four former Guantanamo Bay detainees as they experience rehab at the world’s first terrorism rehabilitation facility, the Mohammed bin Nayef Counseling and Care Center in Saudi Arabia. Some viewers would already scoff at the premise, but as this documentary points out, there are many flaws in that way of thinking for any society. As one of the instructors says in the beginning of the film, “Ok, you punish them. Then what?”

Indeed. One of the four undergoing ‘rehab’ says to the filmmaker: “If I left Guantanamo I will kill Americans.” His statement made more chilling by his broken English and smirking delivery.

Indeed. One of the four undergoing ‘rehab’ says to the filmmaker: “If I left Guantanamo I will kill Americans.” His statement made more chilling by his broken English and smirking delivery.

It took three years to make. Smaker says in the promo material that the film is “a complex and nuanced exploration of the men we have heard so much about but never heard from.” Well, not unless you count the finger-wagging lectures delivered on videos several terrorists have made, and if you don’t count as ‘speaking’ the violence perpetrated by terrorist groups.

While competently made, the film lacks a clear focus and narrative. Towards the end it meanders and we are left in a limbo of ethical considerations.

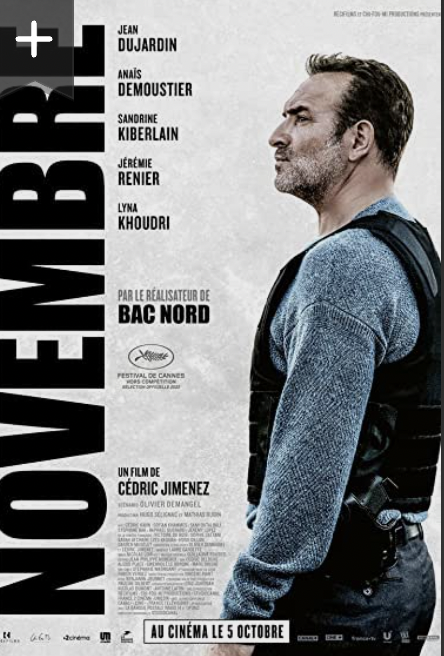

A second film based on real terror events has also just reached Australia (May 11). Titled November, this Cesar award nominated dramatisation follows French anti-terrorist police in the wake of the November 13, 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, which killed 130 and left 350 injured. (Can a life sentence serve justice?) It’s a ‘race against the clock’ thriller tracking one of the biggest manhunts in history, directed by Cédric Jimenez. The film doesn’t show the horror of the attacks but focuses on the five days in which the anti-terror unit tracked down the terrorists.

A second film based on real terror events has also just reached Australia (May 11). Titled November, this Cesar award nominated dramatisation follows French anti-terrorist police in the wake of the November 13, 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, which killed 130 and left 350 injured. (Can a life sentence serve justice?) It’s a ‘race against the clock’ thriller tracking one of the biggest manhunts in history, directed by Cédric Jimenez. The film doesn’t show the horror of the attacks but focuses on the five days in which the anti-terror unit tracked down the terrorists.

“The police investigation was a daunting task and in terms of responsibilities it created an incredible tension for this (police) service,” comments director Jimenez. “The script talks about that. That’s what made me want to make it. I put myself in the shoes of the investigators and wondered how I would react to the obligation of the result and the fear of disaster if that result was not achieved.” More so than with common criminals, catching the terrorists responsible was crucial to avoid further terror attacks by them but also from a moral, psychological and political point of view. The terrorists could not be seen “to get away with it”. Society wants a ‘justice’ ending.

Common criminals do not commit crimes for ideological reasons, even if some acts of rape are committed as part of war and yes, in ideological conflict settings. Ideology does not drive bank heists or online fraud scams or non-terrorism driven murders. Terrorism is a political weapon aimed at civilians to bring about a political outcome – which is why terrorists often refer to themselves ‘freedom fighters’ and the like; much depends on the context and your viewpoint. Yet even after the onslaught of Islamic terrorism in recent times, western society has not developed a practical and humanely acceptable way of punishing terrorists. Those caught, tried and sentenced are simply lumped in with other criminals and imprisoned.

Criminals know that they breaking the law and may even feel some level of remorse; some give up their life of crime. Terrorists break laws and only very rarely abandon the ideology which is their cause.

Hambali’s hearing will mark the start of a pre-trial process that could last for years and which Hambali’s lawyer, Jim Hodes, believes is unlikely to ever result in a formal trial of his client.

Yet citizens baulk at doling out punishment even to terrorists if the courts have not found them guilty.

Variety’s Tomris Laffly takes a pragmatic view of the film Jihad Rehab: “Despite some rare accounts of people who’ve faked their way through the 12-month program just to rejoin al-Qaeda right after, the Mohammed bin Nayef Counseling and Care Center seems, at first glance, mostly to work in its mission to provide a transformative halfway house of sorts for former Guantánamo Bay detainees.”