Andrew L. Urban

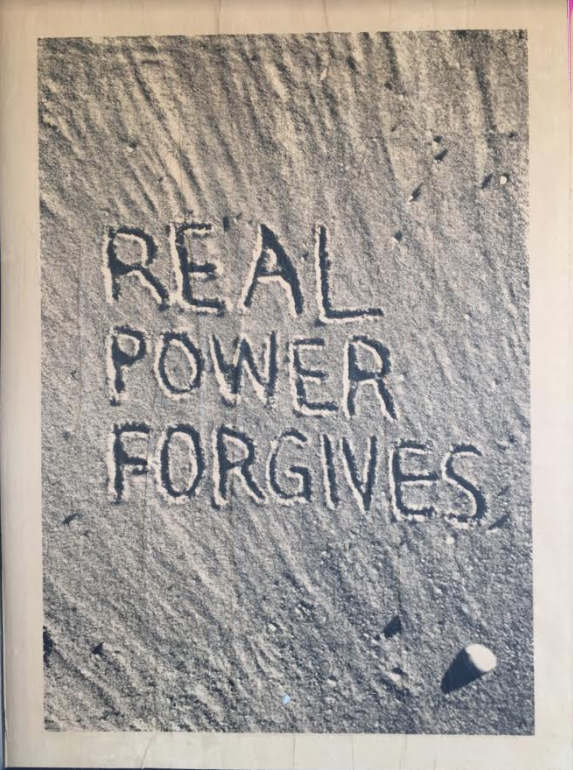

The incongruity made as much of an impact as the poster itself, on a wall along a few other posters in bustling Railway Square, one of Sydney’s least attractive environs. But I was most impressed with the simple truth it paraded for anyone to see – maybe I was the only one. I was certainly the only one to stop and take a photo of it. Real Power Forgives …. I tried to discover the context, but the adjacent image of an unidentified male offered no clue. It doesn’t matter; those three words need no context.

Why I found it so arresting is that I have always believed this as a mantra that you may, if you wish, trace back to the teachings of Jesus and the turning of the other cheek, but more pertinently, it is a sentiment that has percolated through humanity down the ages, from a time BC. It is also the secret, in my humble opinion, to Australia’s uneasy relationship with those indigenous citizens who want to burn the place down and who claim a grievance that won’t heal.

Why I found it so arresting is that I have always believed this as a mantra that you may, if you wish, trace back to the teachings of Jesus and the turning of the other cheek, but more pertinently, it is a sentiment that has percolated through humanity down the ages, from a time BC. It is also the secret, in my humble opinion, to Australia’s uneasy relationship with those indigenous citizens who want to burn the place down and who claim a grievance that won’t heal.

Regular readers of The Spectator Australia may remember a cover story of mine from September 2, 2017, Apology unaccepted, in which I argue that Australia has made and continues to make many apologies: White Australia has long been sorry, in every possible way, for the then colony’s wrongs, even wrongs that may not have seemed so wrong at the time, even those wrongs that were committed with best intentions. In hindsight, we are all very sorry and have said so publicly, sincerely. Almost daily, it would seem. So much apology, so little response.

And I asked then, as I do now, Where was the day that marked that vital, redemptive response to ‘sorry’, the sign that the sorry was heard and accepted, that those wrongs, while never forgotten, would now be laid to rest and ‘forgiven’?

Author Douglas Murray has a sub-chapter on Forgiveness in his powerful and important new book, The Madness of Crowds (Bloomsbury), in which he quotes Hannah Arendt on the subject: Without being forgiven, released from the consequences of what we have done, our capacity to act would, as it were, be confined to one single deed from which we could never recover; we would remain the victim of its consequences forever, not unlike the sorcerer’s apprentice who lacked the magic formula to break the spell.

This seems a painfully accurate snapshot of where we are in Australian society today.

Murray goes on to make a devastating point: This was a truth before the rise of the internet, but how much truer it has become since. One key to addressing this lies in historical rather than personal forgetting. And historical rather than personal forgiveness. Forgetting is not the same thing as forgiving, but it often accompanies it and certainly always encourages it. Terrible things are done, by a person or a people, but over time the memory fades. People gradually forget the exact details or nature of a scandal. A cloud surrounds a person or an action and then that too dissipates among a mass of new discoveries and experiences. In the case of the worst historical wrongs the victims and perpetrators die out–the one who gave offence and the person to whom offence was done. Some descendants may remember for a time. But as the insult and grievance fade from generation to generation those who hold on to this grievance are often regarded as displaying not sensitivity or honour but belligerence.

It is that apparent belligerence that is at the root of my concern for this country’s relationship with its first peoples. Perhaps it is especially noticeable to an immigrant such as me; I don’t know. But the poster in Railway Square is a reminder that forgiveness is not a sign of weakness; on the contrary. And perhaps the context I sought can be found in that it is on display at the main physical connection and communication point of Sydney – Central. In the scheme of things to do with our seemingly unresolvable relationship with Indigenous Australians, it is perhaps the central issue.

That word “Railway”.

My intention is not to detract from the significantly meaningful article. The fact that this poster is in Railway Square prompted me of another relationship of forgiveness. When I saw your photo, my mind also went to the Eric Lomax Story in the film The Railway Man, which maybe you have reviewed at some time?

Maybe these words, “REAL POWER FORGIVES” explain how it was that Eric was able to sustain his survival mode and, forgive.

I’ve watched the movie perhaps 3 or 4 times. Each time it moves me immensely and deeply. I must read Eric’s autobiography. Usually, with movies based on true stories, my preference is to read the book first, as I feel movies at times necessarily omit smaller details. Yet, if I’ve read the book, I can mentally fill those in as I watch the film.

“… Based on the remarkable bestselling autobiography, THE RAILWAY MAN tells the extraordinary and epic true story of Eric Lomax (Colin Firth), a British Army officer who is tormented as a prisoner of war at a Japanese labor camp during World War II. Decades later, Lomax and his beautiful love interest Patti (Nicole Kidman) discover that the Japanese interpreter responsible for much of his treatment is still alive and set out to confront him, and his haunting past, in this powerful and inspiring tale of heroism, humanity and the redeeming power of love. (c) Weinstein”

https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/the_railway_man